WPF Multithreading with BackgroundWorker

UI libraries in general have always been single-threaded. This means that you can access the UI controls only from the thread that created it (thread-affinity). When running long-running operations you would typically use a background thread to do that job. However progress needs to be reported on the UI and the user needs to have a way to cancel the operation. Doing that from a background thread is not possible and hence you have to jump threads, ie. from the background-thread to the ui-thread.

In WPF you can do that with the Dispatcher using Dispather.BeginInvoke(). This allows a background-task to put a delegate on the Dispatcher queue which will be then invoked on the UI thread. However this approach by itself does not allow reporting progress or user-cancellations. You will have to build a component that uses the Dispatcher.BeginInvoke() to provide this functionality, using a technique described in this MSDN article.

The good news is that you really don’t have to write such a component since one is available already: the BackgroundWorker class introduced in .Net Framework 2.0. Programmers who are familiar with WinForms 2.0 may have already used this component. But BackgroundWorker works equally well with WPF because it is completely agnostic to the threading model. BackgroundWorker provides the facilities that I mentioned before: progress reporting and user-cancellation and makes it very convenient to use. If you are not familiar with this class, have a look at this article.

The internals

Under the covers it makes use of some new classes introduced in Framework 2.0, namely the SynchronizationContext, AsyncOperation and AsyncOperationManager. I found this great article by Leslie Sanford at CodeProject which describes these classes. In short AsyncOperationManager is the central class that makes use of the other two. When you call BackgroundWorker.RunWorkerAsync(), its the AsyncOperationManager that collects the synchronization-context of the invoking thread and knows how to marshall calls to the UI-thread from the background-thread.

The real trick happens with the SynchronizationContext instance. A WinForms app would provide its own context: System.Windows.Forms.WindowsFormsSynchronizationContext, which derives from SynchronizationContext and knows how to Send/Post to the UI thread. Similarly in WPF we have the DispatcherSynchronizationContext that does exactly the same job.

BackgroundWorker uses the AsyncOperationManager, which internally gets an instance of DispatcherSynchronizationContext when a WPF app starts up. Thus when you call RunWorkerAsync(), the right context is picked up. Inside the DoWork delegate, when you call BackgroundWorker.ReportProgress(), the call internally marshalls it to run on the UI thread.

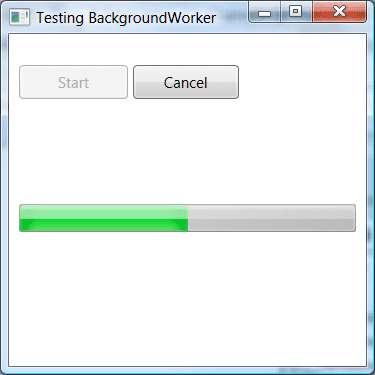

So with this powerful combination of classes, multithreading in WPF only got so much easier ;-). I have attached a simple project that demonstrates the use of BackgroundWorker with WPF.

Download Zip

Download Zip